With week 1 in the rear view, I wanted to provide a peek behind the curtain and examine my best ball portfolio. In this article I’ll be discussing my player exposures, some specific roster construction examples, things I feel I did well in my drafts, and things I want to improve on for next season. We’ll start by setting the table with my exposures on DraftKings:

Above is how I played the first two rounds across all of my entries on DraftKings. In total I drafted 237 teams on DraftKings in many different tournaments, including some timeboxed tournaments (tournaments that were not open for the entire summer). The majority of my higher stakes action came on DraftKings as well, in the $555 contest and some of the single entry and 3 max tournaments they had, purely because their high stakes tournament formats were far superior to the offerings on Underdog.

My exposures through the first two rounds are indicative mostly of roster construction preferences that I have, rather than specific player takes. I strongly preferred getting two WRs through the first two rounds, based on my perceived steep drop off at the tier break of Higgins and DK Metcalf. I also did not see a huge difference in many of the 2nd and early 3rd round RBs compared to RBs that were available later (Jahmyr Gibbs, Travis Etienne, Breece Hall, Kenneth Walker, and JK Dobbins to name a few).

One of my largest stands in the first two rounds was on Dolphins WRs, which was also largely systemic. I viewed Tua as one of the most mispriced players for the entire draft season, which led me to opting to open the Tua stack option at a high frequency. The market over confidence in Tua’s injury risk suppressed his price and led to inferior fantasy QBs being drafted ahead of him. I personally had Tua in the same tier as Joe Burrow, Justin Herbert, and Justin Fields. I felt like Tua and Trevor Lawrence had some Freaky Friday ADP swap going on, which is reflected in my QB exposures. Of course with the hindsight of week 1, that take looks like it’s aging well. I don’t want this exercise to turn into victory lapping, because the NFL is extremely chaotic and week 1 is just a single data point.

Some of my biggest fades in the first two rounds were all three of the elite QBs. The prices on DraftKings were simply unpalatable for me, given the opportunity cost in having to pass on players like Waddle, Olave, and Pollard. When coupled with how I viewed the QB landscape (extreme values in players like Tua, Mac Jones, Sam Howell, Desmond Ridder, Geno Smith, Kenny Pickett, and Anthony Richardson) it made sense that I would only be getting one of the big three QBs at big value. You’ll notice Josh Allen is the only one of the elite three QBs that I don’t have ADP value on. In review of my Josh Allen teams, there were multiple instances of absolute mad men in those draft rooms, taking elite QBs in the first round, and sometimes auto drafting four QBs in their first four picks. A big part of maximizing your value in each draft is paying attention to what is happening in your specific draft room. In drafts where I knew QB scarcity would be cranked up because of a couple loose cannon drafters gobbling them up well ahead of ADP, I prioritized getting an elite QB because the advantage it gives in a draft room like that is significantly exaggerated. If one team has Hurts, Mahomes, Lamar, and Burrow, the remaining 11 teams will be much weaker at QB than in an average draft. By taking the last remaining elite QB, I secured an advantage at the position against the 10 live teams in the league. In draft rooms like that I can anticipate capturing some value at the skill positions later in the draft based on the QB scarcity causing other drafters to take their QBs early, for fear of being locked out at the position by the maniac(s) taking multiple QBs in the first couple rounds.

Something that might look a little strange in my exposures is the huge disparity between Tee Higgins and Devonta Smith, two WRs who I (and the market) had very close in their ranking. This was partially randomness, but also because I often broke ties in favor of Tee Higgins at the 2/3 turn. I favored Tee due to his playoff week correlation with Justin Jefferson (on teams where I had Jefferson), my attempt to set up the Bengals double stack (on teams where I had Chase), the increased optionality of having a QB stacking option available when selecting Higgins compared to Smith (Burrow was almost always still available for a potential stack with Higgins, where Hurts was rarely available for a potential stack with Smith), and finally a very small weighting towards Higgins based on the mutually exclusive nature of Justin Jefferson and Ja’Marr Chase, with Higgins offering negative correlation to Chase, and Chase teams being more likely to have similar player combinations to Justin Jefferson teams compared to AJ Brown (the negative correlation to Devonta Smith) teams based on what side of the draft board those players were on the entire draft season. In hindsight I definitely prefer to be over on Higgins, but the rate at which I did it is probably too extreme. To help rectify this issue for future drafts I’ll use more randomization with weighted frequencies based on what I think is the correct frequency for certain player 1v1s. For example, if I determine that I want to be 60/40 Higgins vs. Smith, then I’ll use a random number generator to select a number from 1-10, any number above a 6 is Smith, everything 6 and lower is Higgins.

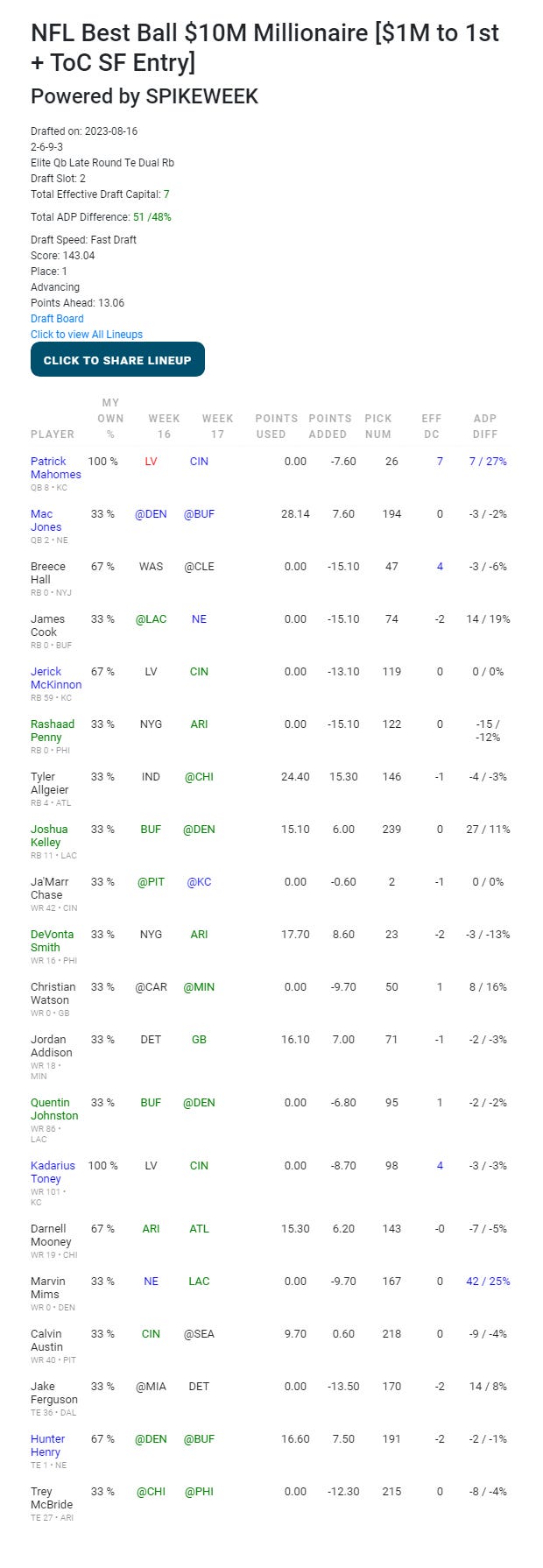

The last topic I want to touch on from the first two rounds is how I played the elite TE position. With only 3% Travis Kelce compared to 18% Mark Andrews, it’s clear which of the two super elite TEs I preferred. Unlike my Higgins/Smith exposure, I feel like I properly executed the way I wanted to play Kelce relative to Andrews. One of my primary theses regarding Kelce is that there is no player in the 1st round that would hurt your advance rate more in the event of catastrophic failure. A large part of this is based on how drafters typically play the TE position when drafting Kelce, often only taking 1 other TE, frequently with low draft capital. The next prong of my Kelce fade was that in my limited Mahomes exposure, I wanted an outsized opportunity to have Mahomes be a potentially under represented QB in the playoff weeks, even if he himself had a great season. With such a high Mahomes+Kelce combinatorial ownership by the field (our ownership projections had Mahomes+Kelce occuring in 32% of drafts in the $10 Milly Maker tournament), in the outcomes where Kelce fails, Mahomes sees his advance rate artificially suppressed. I saw the path to extremely outsized +EV playoff teams in the event that I advance a Mahomes team without Kelce, in a season where Kelce fails. Here’s an example of a team I drafted executing this strategy (my ownership numbers in the lineup below are only reflecting my three Mahomes teams):

Kelce was only half of the equation though when it comes to my significant overweight Mark Andrews position. I wish I could say it was all of my own accord that I got to that stance, but sometimes the smartest thing you can do as a best ball drafter is listen to other analysts that you respect. That’s exactly what I did here, aggressively correcting my Mark Andrews position that was approximately even with the field, to significantly overweight after reading Pat Kerrane’s “Mark Andrews Checks All the Boxes” article. With my fade on Kelce, bullish evidence for Mark Andrews, and my belief in Elite TE as a very potent best ball strategy for the playoffs (also informed by quality work from Pat Kerrane’s Elite TE article), my exposures on those two players begin to make a little more sense.

Moving past the first two rounds, let’s examine my QB exposures, as I mentioned earlier that my view of the position greatly impacted the way I structured my draft strategy.

I already discussed why I was out on the three elite QBs going in the 2nd round, citing opportunity cost. Opportunity cost is the exact reason I warmed up towards taking QBs in the next tier, simply because the opportunity cost of choosing between Deebo Samuel and Lamar Jackson for example was much more reasonable than taking Mahomes over Pollard. You’ll notice I was very price discriminate when taking the early QBs, with significant positive ADP values on all QBs with an ADP earlier than 60 (other than Josh Allen, as I previously discussed the phenomena that led to my ADP for him). This is because market efficiency is at its highest in the early rounds of drafts. As we get later in draft rounds, the market is not very efficient at pricing players, which is why I was not as discriminate with the prices I got on some of my later QB targets. You can see my reasoning for this reflected in my Spike Week Draft Capital Model Explained article. For readers that are newer to best ball, you might be looking at my QB exposures and thinking “This guy is an idiot, Desmond Ridder, Mac Jones, Sam Howell, and Kenny Pickett all suck!”. To that I would say, it’s possible, even probable that you’re right. I wouldn’t be very excited to draft any of these QBs in a traditional managed fantasy league. However, the lower a QB’s draft capital, the more room there is to run on the upside in those unlikely outcomes where they are better than the market thought (see Geno Smith last season). I had reason to believe that my late round QB targets all had enough of a chance to substantially outperform their draft capital that I felt it was worth a shot, especially in the large field, lottery style best ball tournaments that many of these drafts occurred in. Through some combination of a number of factors, each of these QBs checked enough boxes for me:

- Year two QB (higher probability of breakout than any other year for QBs)

- Surrounded by good weapons, with draft capital for their targets disproportionate to the QB draft capital relative to other QB prices

- Some rushing upside

- Significant change in offensive system

I also did some modeling during the offseason using historical BBM data. I trained my model based only on information that was available at the time of each draft, focusing specifically on how the market priced players and team level correlation, with the model output being projected points for the regular season for a best ball team. I found some interesting results that helped to inform my QB draft strategy for this season. The model showed the highest variance in its projection of regular season roster points for team stacks with extremely high cumulative draft capital, and extremely low cumulative draft capital. My interpretation of this data was that in general, the market has historically been efficient at identifying the best QBs. When they are successful, your team is likely very good if you stacked them with their teammates. When expensive QBs fail, your team is very likely dead due to the outsized amount of draft capital you spent on the entire stack. However, for low draft capital team stacks a similar level of variance meant that I could get the same upside necessary to advance a best ball team by stacking up cheap offenses. That is one of the reasons why the Patriots were one of my favorite offenses to stack this season.

Another macro strategy that I utilized in my drafts focused on maximizing my optionality in drafts when possible. I accomplished this by creating a “Weighted Outs” metric, that counted the number of players remaining in a draft room that had some level of correlation with the specific player I was calculating Weighted Outs for. I would then take the raw count values and weight them based on a couple factors, including their draft capital, the value I placed on their specific correlation (team correlation > week 17 > week 16 > week 15), along with my relative need for each position group in that specific draft. In general, if I liked two players a similar amount (after considering all other tie breaking factors), I would lean toward taking the player that gave me more stacking options later in the draft through the weighted outs metric. What this allowed me to do was capitalize on falling values in drafts to the highest level of effectiveness that I could, knowing that I often had many viable QB stacking partners available later in the draft. Typically I would only select a QB if they were significantly after ADP, their tier would be depleted before my next pick, or they completed a high priority stack for me.

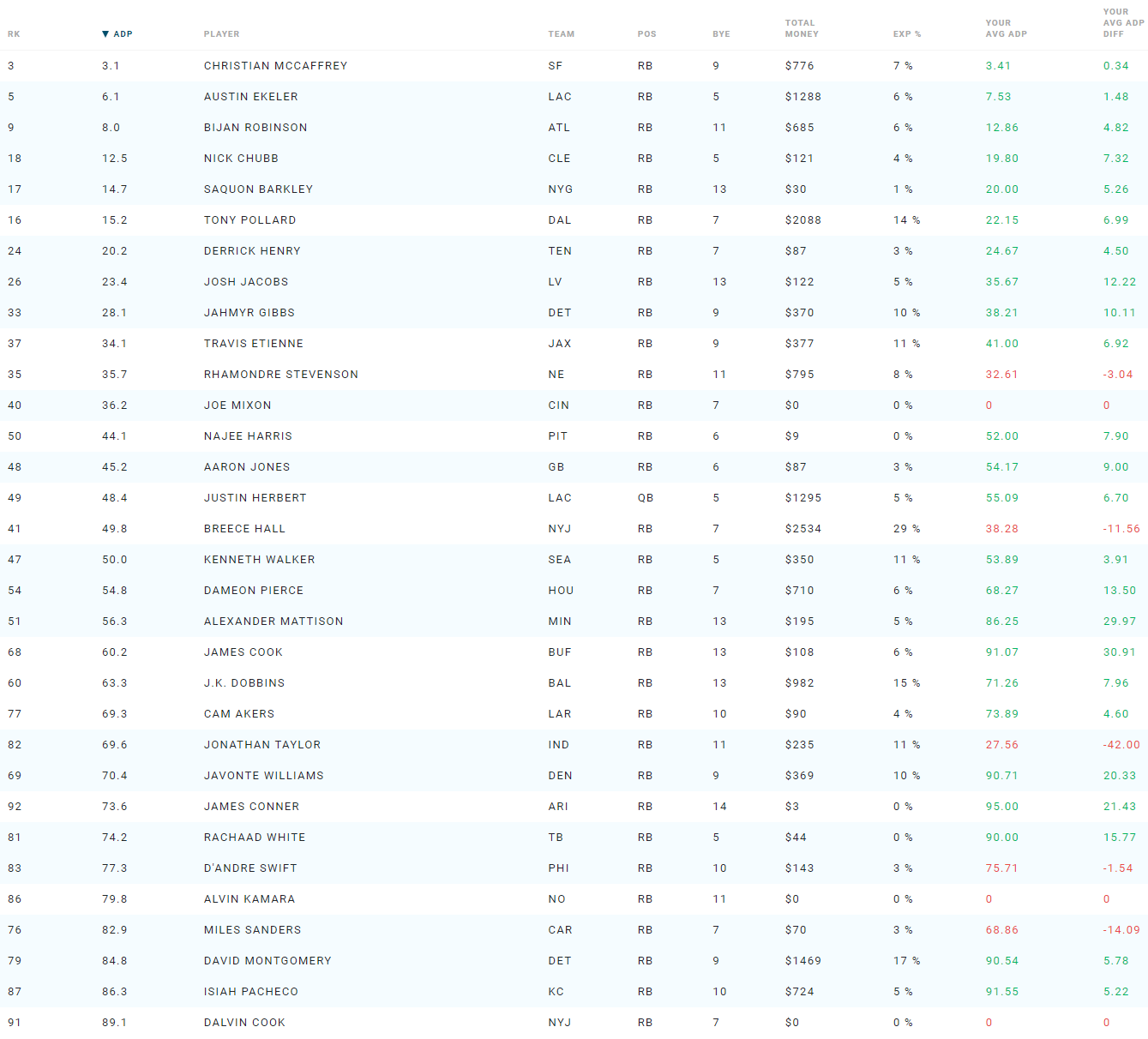

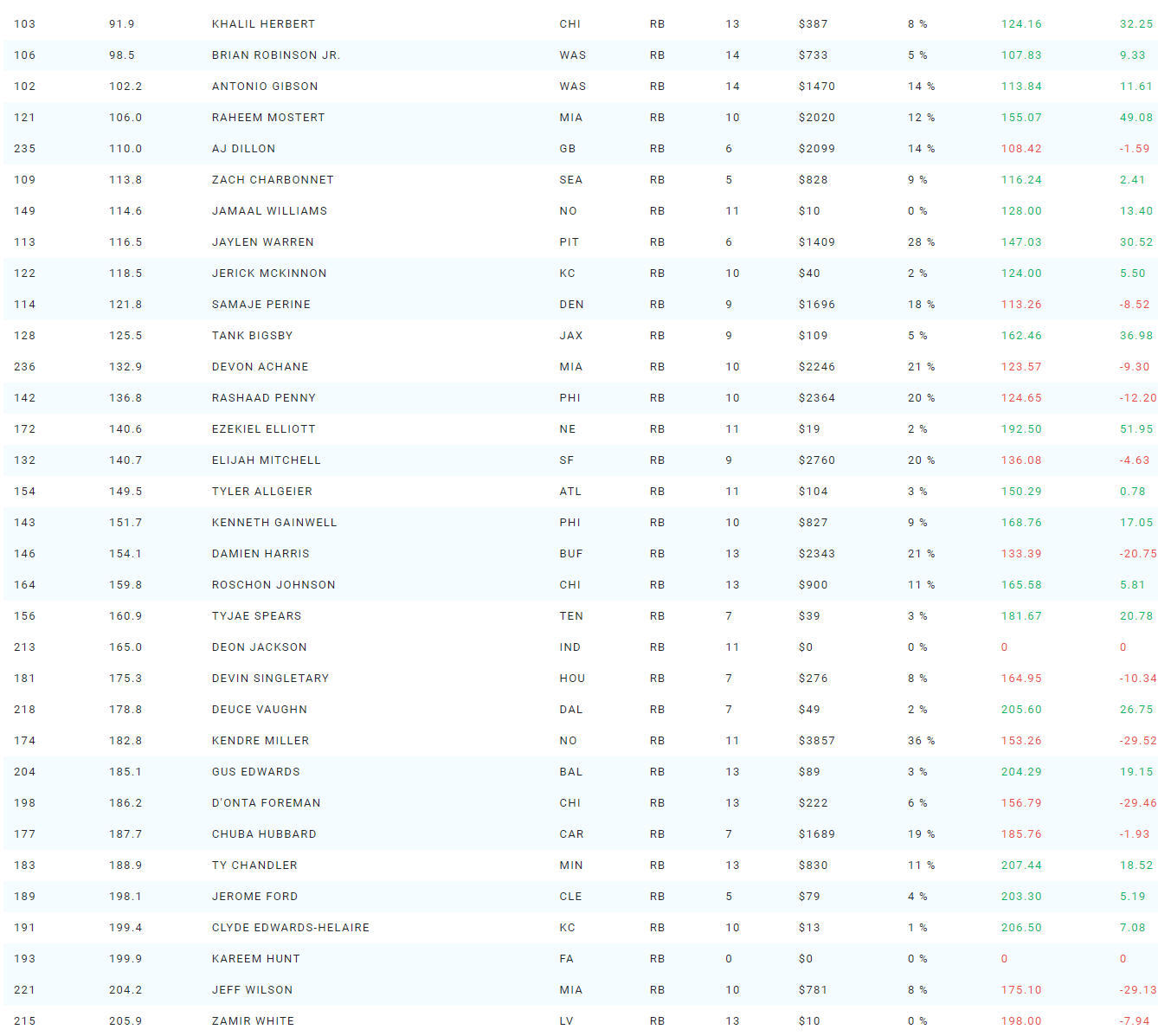

Next stop on the tour de exposures is RBs. I’m including all the RBs by ADP, because I want to highlight not only my overweight positions but my fades as well. In the last exposure image here I’ve omitted some of the extremely late RBs because fading guys like Trey Sermon and Abram Smith isn’t worth much discussion.

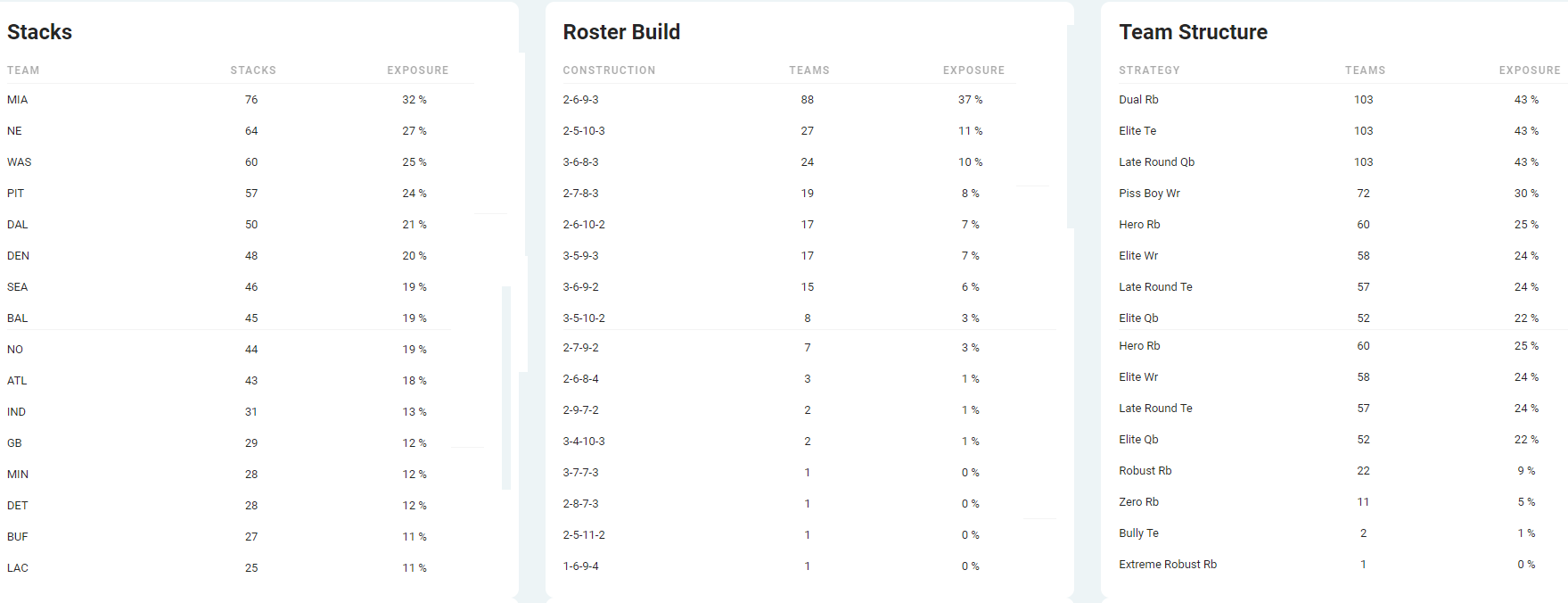

Ok, that was a lot of exposure images. Before I dive in to specific player analysis and reasoning behind my overweight/underweight positions, I need to properly frame the way I attacked the position by showing my roster construction frequencies.

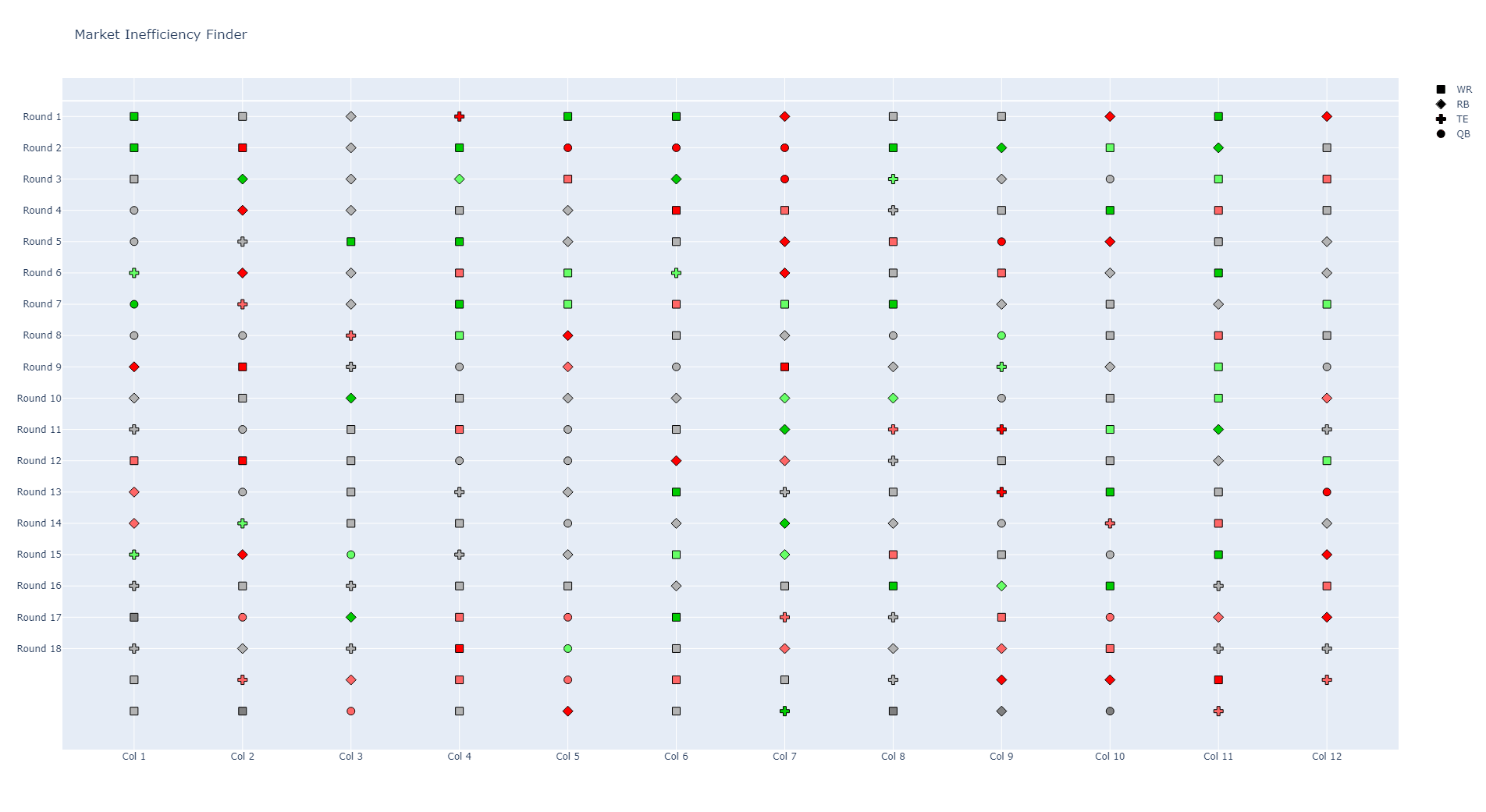

You’ll see I was very heavy on Dual RB and Hero RB builds, but from my specific player exposures it’s clear most of the RBs in those builds came from rounds 3-5. My read on the RB landscape this season was that due to the market wide effects of rising WR prices, some valuable RB gems got pushed down into what would have historically been considered “the dead zone”. WRs in that range of the draft were in a much flatter, very large tier in my opinion, where the few RB targets that I wanted stuck out like diamonds buried in piles of shit. On DraftKings some of my favorite WR values existed in rounds 6-9, so it meshed very well with the way I wanted to attack both positions. You get a good feel for the draft landscape when you draft over 800 teams, but if you’re not super plugged in to the market (I took a couple vacations this summer where I wasn’t drafting, or closely monitoring ADP changes) then utilizing a market inefficiency tool can be a really useful way to get a 10,000 foot view of the draft landscape and help you formulate a plan of attack. Here’s a sample of the tool I created for myself to identify market inefficiencies relative to my rankings:

This is an outdated snapshot of the draft landscape, but I felt like it was worth sharing to give some insights to the types of things I’m considering when coming up with my strategies. We’ll look at adding a tool like this to the Spike Week suite of tools for next season.

Alright, back to my RB exposure analysis. You’ll see I’m fairly price conscious, especially early in drafts when draft capital is highest. The only negative ADP values I have in the first 6 rounds are fallers (Rhamondre, Breece, JT). You may notice that I have nearly 3.5x the field on Breece Hall. Unfortunately I waited too long to write this article, as I’ve heard other analysts I respect banging the drum for Breece Hall as the RB1 in 2024 (shout out Ben Gretch). I do have to include at least some receipts that I had identified Breece as an extreme value that I wanted to plan my 2023 drafts around way back in January:

We’ll see how well this take ages, but I still believe in the thesis. If I wind up eating crow on Breece Hall, it’s a bet I’m comfortable eating crow on. I never intended for this article to be a bag defense piece, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t share some more of the excellent work that Pat Kerrane did in his Legendary Upside in the Dead Zone article, where he lays out the bull and bear case for Breece.

My other huge position at RB is rookie Kendre Miller. Kendre checked all the boxes for me as a fantastic late round RB target. I want this article to focus on a macro look at my portfolio as a whole, and not to get derailed by individual player takes. If you are interested in some of the things that convinced me to heavily target Kendre Miller, the article “This Method for Crushing Underdog Tournaments With Rookie RBs is Counterintuitive but Powerful” by RotoViz’s Blair Andrews does a good job laying out the thesis behind the play.

While I don’t regret my Kendre exposure, the one thing I do regret is how I chose to play it from a portfolio perspective. Early in draft season I try to aggressively target players that I think have an outsized chance to substantially rise in ADP. Kendre certainly fit the bill for me there: an electric rookie, taken with early draft capital (the 4th overall RB off the board, with an early 3rd round pick), with very little talent in front of him on the depth chart (I was not scared of replacement level RB Jamaal Williams or past-his-prime, suspended Alvin Kamara). I had Kendre pegged as a player with a high likelihood of increasing in cost. My over confidence on that specific outcome is what ultimately led me to have a position that could have been more favorable when considering the cost I paid for him in drafts. I didn’t anticipate the market double counting Kendre’s injury recovery timeline, as it was well documented he was rehabbing a knee sprain during the offseason and likely wouldn’t be available for the very start of camp, yet he fell precipitously when news that he wouldn’t be active the first day of camp broke. When Kamara’s suspension was announced as only three games Kendre fell again, briefly sliding to the very last few rounds after he suffered another minor injury (which he was back from less than a week later).

What I’m trying to convey with the Kendre ADP rollercoaster recap is that I didn’t properly account for the market over reacting to the downside, against my initial thesis of a sharp rise for Kendre. If I hadn’t positioned myself with such heavy Kendre exposure at the outset of draft season I would have happily gobbled up all the Kendre my greedy little hands could grab as his price fell. Unfortunately, I was at an impasse where my personal risk tolerance for an individual player ownership was in direct conflict with my desire to acquire targets I valued highly at the best prices. Ultimately I passed on Kendre more frequently during the stretch when he was at his lowest prices than I did when he was more expensive. This is never the way I would intentionally draft a player, as I think getting the best price on players is extremely important from a portfolio perspective. However, the damage in this case wasn’t nearly as bad as it initially felt. The draft capital I lost taking Kendre at his expensive prices was relatively small, as draft capital drops off sharply in our model. Still, the point of this exercise is not to say “it actually wasn’t that bad” in places where I could have played better, but to learn from my mistakes and improve as a drafter for the future. My take away from the Kendre situation is that in the future even if I am extremely certain of a player’s likelihood to rise, I won’t ever box myself out of being able to take more of them in the event that they fall. I’ll accomplish this by defining an ownership threshold I’m comfortable with for each player given a range of outcomes for their price, as well as their on field performance. For Kendre I think in hindsight that maximum ownership number would be 40%. That’s not to say I want to set out with a goal to get to 40% Kendre Miller, but that if given the opportunity based on the price he is available at, I would comfortably draft him at ADP until I got to a point where I would need to begin passing on him often if he were to fall, so as to not surpass 40% ownership by the end of the draft season.

My quick thoughts on the unsigned veteran RB group of Hunt, Zeke (unsigned the majority of the offseason), and Fournette are that of the three, Fournette was the least washed player. Hunt and Zeke were both dreadful in their advanced metrics last season, and while Fourntette was no shining star he was at least serviceable and seemed like he could land in a situation where he could reasonably get some passing game work and potentially other high value touches. I think from a process perspective I’m fine the way I played this group, as even if Hunt and Zeke signed and delivered substantial closing line value on their ADP (as Zeke did when he signed with NE) we still have the Julio Jones corollary to worry about: CLV does not guarantee fantasy points.

The last RB I need to spend some time on before we move on to WR is my personal flag plant of this offseason in Justice Hill. Sometimes fantasy football doesn’t need to be hard. If you read the reports coming out of Ravens OTAs, Justice Hill was quite literally the only RB at OTAs that was expected to even be on the final 53 man roster. Not only was he getting valuable reps to showcase his talents with new offensive coordinator Todd Monken, he was looking very good doing it if the beat reporters are to be believed. Fast forward to training camp, and JK Dobbins was holding in leaving Justice Hill to compete with 28.4 year old Dust Edwards (whose hasn’t put up positive EPA numbers for three years), the corpse of Melvin Gordon, and UDFA Keaton Mitchell, who best profiles as smaller Justice Hill, with a worse size adjusted speed score. Justice Hill checked all the boxes for me that got me to draft an absurd 40% Jerrick McKinnon last season, who peaked during the fantasy playoffs and contributed to my above average playoff weeks advance rate. Justice (and Jerrick) are both plus athletes, that profiled as the best pass catching back on their respective teams, who had early career opportunities derailed by injury. Neither profile as a large enough back to carry a bell cow workload (McKinnon is closer, as he is 10 pounds heavier than Hill), but a bell cow workload isn’t necessary for plays like this to hit. When we’re drafting players in the last round of our draft, we’re looking for guys that can get on the field and potentially deliver a difference making performance for fantasy. These two backs are great examples of profiles that we should be looking for at the end of best ball drafts because they can command high value touches on high scoring offenses.

To dove tail with Justice Hill, I need to take an L on my lack of Kyren Williams exposure. Kyren doesn’t check all of the same boxes that Justice does, but he did have much more certainty in his role late in the offseason. I liked Kyren, I really did! Even though my exposures say otherwise. To be perfectly honest I was late to the Kyren party and I already had completed the majority of my drafts (I was probably through ~600 teams by the time I added Kyren as a high priority late round target). Kyren kept getting sniped from me! The cat was out of the bag, and the market got wise to Kyren. I can only blame myself, as there were many times earlier in the draft season that Kyren sat in my queue as a potential last round dart throw and I randomized who I selected. I guess the gods of randomness really disliked Kyren (and they loved Justice Hill, Calvin Austin, and Cedric Tillman).

At the outset of this article it wasn’t my goal for it to be this long, but I wanted to do it Justice (pun most definitely intended). I’ll be breaking this up into a series, with my WR and TE exposures to come in part two. My Underdog and FFPC exposures will come in future articles as well. At this point, you can come up for air, dear reader. I’ll have part two available for you soon.