If you’ve read any of my macro strategy Best Ball content here, or listened to any of our media content, you probably know I am a big fan of using analogies or examples from outside the game of football or best ball to think through particular variables of this silly game we play.

If this is your first time, buckle up.

One of the more hotly debated subjects in best ball is the idea of uniqueness. I think we all understand that there is inherent value in being different from our opponents in a peer-to-peer game like Best Ball. We are drafting against thousands of other humans, we are drafting the same NFL players as everyone else, and we are drafting them in essentially the exact same order in every draft.

Clearly, if we are trying to beat all these other humans with our teams, we don’t really want them to be the exact same combinations of the exact same players. But we also don’t want to make *worse* teams just for the sake of being different. If we create a bunch of teams that are much worse than our opponents just to be different, we are really just being contrarian to be contrarian and not gaining any advantage.

This is probably the subject I have spent the most time thinking about since we started Spike Week years ago. It’s so unbelievably exploitable that our opponents in this game all draft the same players in the same order in every single draft, and thus pair many of the same players together on the same teams…. while never drafting certain combinations of players together… ever.

I’ve noted one of my favorite podcasts in a few different articles here, and yes, I am going to do so again today. On the most recent episode of “My First Million“, a Midwest farmer who started an agriculture newsletter that is making $20+M per year broke down the model they use to make decisions, and I could not believe how perfect it was for this exact subject.

At about the 16 minute mark, Kevin Van Trump details how they compare “value” vs. “uniqueness” of any potential venture they consider. He even pulls up a simple chart that explains the concept very succinctly (more on that in a sec). Long story short, he discusses how they weigh how valuable a business or idea is vs. how unique it is to determine how sound of an investment it would be. Many things can be unique, but they are not highly valuable. Many things can also be highly valuable, but they are not unique.

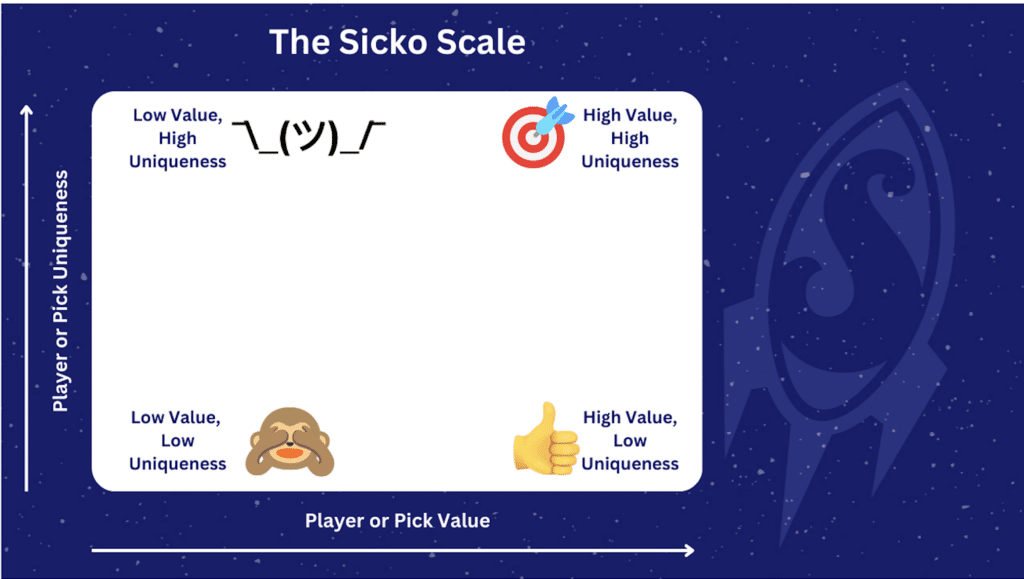

I took his chart and turned it into what I’m calling the “Sicko Scale”. I found it to be a super helpful way of thinking about the picks we make in our drafts and just an overall application of uniqueness vs value in Best Ball.

An example of something is highly valuable but low uniqueness from the episode is a tire business. Tires are extremely valuable. We couldn’t operate in life without tires. Our vehicles and many other products could not function without them. Everyone needs tires, but a tire business is not unique. There are lots of tire businesses in the world and, at the end of the day, tires are tires. If you’re going to succeed with that kind of business, and you can, you are going to have to win in a different way.

Then, you have plenty of things that are highly unique, but they’re not highly valuable. Frankly, a lot of new technology can be this way. Some unique new technology that doesn’t exist, or barely exists, in the current market. But despite its unique offering, it’s not exactly something that everyone needs or adds a ton of value. It’s also probably an expensive product to bring to market, and the longevity is a concern. For example, we have seen this in the crypto space constantly. NFTs became all the rage during the pandemic because it was a super interesting and unique technology. So you saw a ton of projects where folks were applying the technology to low value problems. We don’t need to insert the blockchain into the process of taking our dogs for a walk. Sure, it’s unique, but it’s not valuable. My dogs are perfectly happy on their walks without any NFTs involved.

Both of those examples can have their place, however, in our game of Best Ball. The one intersection of this idea that we *really* want to avoid is “Low Value, Low Uniqueness”. Probably pretty self-explanatory, but if something is not unique AND it doesn’t have value, it’s pretty safe to say we should go ahead and avoid that one.

Where we ideally want to live as much as possible is in the upper right hand corner – High Value, High Uniqueness. Kevin mentions that this is where Apples has often lived, and that’s what has made them so successful. Think about the iPhone, iPod, Mac, Apple Watch, etc. Their marketing for the iPod many years ago was “10,000 songs in your pocket”. The first iPod was released in 2001, and that was something extremely valuable at that time. Music is a big part of human life, but you had to carry around a freaking huge portable CD player back then to listen to music on the go, and you had to have these huge binders of CDs. Clearly that brought a ton of value to the consumer, but it was also as unique as it gets at that time.

So, what does this mean for Best Ball?

The Sicko Scale – How to Combine Player Value & Uniqueness

As you see above, I just slightly tweaked Kevin’s model for our game of Best Ball. It’s rather crazy how perfectly it fits for this idea of uniqueness in Best Ball. But there are a few specific nuances that stick out the most.

What is Value?

This is probably the most important element to the conversation. Value is discussed in Best Ball as strictly ‘ADP Value’, but that’s not the whole story. ADP is just price. If our picks in Best Ball cost money, the ADP would be the sticker on that CD that tells us how much it costs. Price is just price, and it doesn’t mean something has value. It also doesn’t mean something doesn’t have value.

Price, or ADP, in Best Ball definitely has a positive or strong correlation to value. Generally speaking, in the fantasy football market, the higher up the ADP list a player is, the more valuable they are. But they aren’t necessarily more valuable on every single team you draft, and we also all define each player’s value differently. And those aspects are both the most fun part and also the most difficult part of this whole game. If you’ve followed me or the Spike Week community at all, you know that I value these more expensive running backs less than the market does. That doesn’t mean I’m correct, but the Josh Jacobs’ of the world are less valuable to me because of several market dynamics, including the quality of the running backs available later in drafts, as well as the steep fall of in “value” of the wide receivers as the draft goes on.

But that’s also just discussing the idea of value in a vacuum. Once we’ve made some selections onto a team, or even once we’ve drafted a certain number of teams in our portfolio, the value of these picks change. For example, if I select Josh Allen in the 3rd round, the value of the other elite QB options takes a hit for that specific team. I’m probably creating a worse team if I add Lamar Jackson and Patrick Mahomes to my Josh Allen team. Using our tire example above, we know that tires are a valuable commodity, but if I’m in need of a bicycle tire, I am not going to value a car tire at that moment.

It’s super important to separate the idea of “value” from ADP. They are related, and they can be correlated at a super high level, but they are not synonymous.

Buy Value, Not Price

Piggybacking on that, Kevin mentions something that is also super notable here. He discusses how people buy value, not price. It may seem like the same thing, but just because something is cheap doesn’t mean it has value. I could go purchase a bunch of CDs for a pretty cheap price nowadays, but I would never use them. I don’t even own a CD player anymore. And if I wanted to turn around and sell them, I probably couldn’t even sell them no matter how cheaply I priced them. Because they have no value.

On the flip side, if something is very valuable to me, I’m willing to pay a higher price. I have mowed a LOT of yards in my life. It was how I made some spending money when I was a young kid, and as soon as I could see over the mower, my parents had me mowing the lawn at my house. I could save money and continue to mow my lawn myself, but now that I’m older I value saving that time and effort more. It’s not too cheap nowadays to pay for a lawn service, but it’s valuable to me, so I pay it. It’s not cheap, but it has value.

It’s a pretty important distinction to consider for Best Ball in a couple different ways. First, just because a player falls past his ADP does not mean he is valuable to your team. ADP is just price, and just because a store runs a sale on an item doesn’t mean it’s valuable enough to you to buy.

The other angle of value vs. price is in late round players. A framing we as Best Ball players will often use to rationalize our late round picks is “well he’s cheap” or “it’s just a last round pick”. That may seem logical at face value (no pun intended), but it’s a bit of a psychological trap we allow ourselves to fall into. It’s like when you are leaving the grocery store and they put all the junk food and random crap near the checkout line. It’s cheap, and they might even be offering discounts or sales on those items. But if you didn’t already want a Kit-Kat, or maybe you don’t even like Kit-Kat’s, then it doesn’t have any value to you… even though it’s being offered to you cheaply at the end of your shopping trip.

Again, the premise of “value” is mostly in the eye of the beholder. We all value players differently. You like Kit-Kat’s, I like Reese’s and someone else prefers Sour Patch Kids. That’s the fun part of the game. But I don’t like Almond Joy’s. Those are my “Van Jefferson” of the candy selection near the checkout line. It doesn’t matter how cheap they make those Almond Joys, I’m just not interested. I’d rather take a shot on a candy I’ve never tried before (kinda like a rookie WR or backup RB) than take a discount on something I don’t think has any value.

How Uniqueness Fits In

The last frontier of the conversation is how uniqueness plays in here. As we stated at the top, I think we all understand that we don’t just want to draft replicas of the same teams our opponents are drafting. But how we go about drafting unique teams is the key.

Since we want to be in the upper right of the Sicko Scale – High Value, High Uniqueness – there are 2 ideas that stand out to me.

- Creating Unique combos with the highest value players can have the most impact.

- Taking that price discount on high value assets can be the easiest way to navigate to that quadrant of our scale.

Starting with the first point, it feels a bit counterintuitive. You don’t want to deviate from ADP at the start of drafts. Those are the best players and the market is very confident in the order they should be selected. But if we agree those are all the high value assets, it’s pretty comical that we willingly draft them only in the exact same order and paired with the exact same other high value assets.

It’s like if Apple, during their development of the iPod, realized that putting thousands of songs onto this device was important. And they realize that it being small and able to fit in your pocket was important. But they refused to pair those two things together because the current market never cared to put them together up until that point. The power of their product was not just the value of one aspect in a vacuum, it was the value of two things when combined together to create a totally new and unique product.

I get it, you like Puka Nacua more than Drake London in 2024. I have Puka ranked higher as well. But we all value them pretty darn closely. They are both picks we value from pick 8ish to pick 15ish. If I’m willing to draft Drake London, I clearly value him at a very similar price. But I value London because of London. I don’t value London because of the combination of London and whatever player naturally falls in line with his ADP at the 1/2 turn. If I select him with the same player(s) everyone else selects him with, I move down to the bottom right hand corner of the scale. He’s high value, but I’m going to have to win another way because I’m not making iPods anymore, I’m making tires.

That does NOT mean you need to completely avoid the more popular combos. Not at all. CeeDee Lamb and Amon-Ra St. Brown were a very popular combo at the 1/2 turn in 2023. They were great picks! I just wouldn’t want every single one of my CeeDee Lamb teams to have Amon-Ra, and vice versa. Folks often talk about diversifying or mitigating risk in their portfolio, and yet they draft certain players with other individual players a very, very large amount of the time. By doing so, you’re not really diversifying your portfolio. You’re just diversifying your raw individual player exposure. Your portfolio is just as risky and condensed as someone who takes huge individual player stands, you just can’t tell from your exposures page in the app of the Best Ball site you’re drafting on, so it’s out of sight, out of mind.

On that second point, it can feel uncomfortable to manufacture your unique combos. I’d urge folks to try these things out, and we have Best Ball Ownership Projections here at Spike Week that can help you see what the projected ownership is of different player combinations. But even if you aren’t yet comfortable with how to create some of these more unique combos, there are other methods to facilitate this.

These are snake drafts, so sometimes players will fall in a certain room. you are in. I am really trying to lean heavily into Zero RB principles this year, but even I could not pass on De’Von Achane when he fell to the 43rd overall pick. Even for me, a running back hater, he was a valuable asset, and I knew just by selecting him here that I would be adding that uniqueness to the team. The combination of Justin Jefferson, Chris Olave, Malik Nabers and De’Von Achane with my first four picks instantly pushes the team into the upper right hand corner of the scale, so it was an easy choice.

The tough part with this approach, if we never mix it up, is you don’t ever really know if or when potential uniqueness will arise. Most drafts it will not, or at least it will not with our highest value assets. So we can run into issues with our portfolio and with our specific player combinations across our teams if we refuse to consider manufacturing some of that uniqueness and ONLY wait for some extreme fallers. But, when we get it, it’s probably the most powerful way to navigate to the upper right hand corner of the Sicko Scale.

The Other 3 Quadrants

The last point above the Sicko Scale is that it’s ultimately ok to live in 3 of the 4 quadrants. Obviously the upper right is what we are searching for, but so long as we are staying out of the bottom left, we aren’t actively hurting ourselves. In the bottom left, we are just being idiots. Trying to be super crazy and different just do it, and we are probably just bored from drafting so many teams.

But if we are a few rounds into our draft, and we are in the upper left or bottom right, we can still create good teams. We just need to ensure we know that’s the quadrant we are in. If you’ve got a few high value players at the start of the draft, but they’re frequently drafted together, that’s ok! But at some point, we do want to consider the uniqueness of that team. And the longer we wait to address that, the less powerful the uniqueness becomes. Drafting some last round guy who is rarely drafted is cool and all, and we absolutely should be doing that. But it’s just less impactful to our uniqueness overall because it’s our lowest value asset.

On the flip side, if we take a hit in the value of our collection of players, but we gain uniqueness, we need to know that. It’s very easy to fall from the upper left to the bottom left, so it’s a potential slippery slope, but it’s not insurmountable.

We just can’t avoid tumbling down that slope if we aren’t aware that it’s slick. Which, funny enough, is the same for the entire premise of the Sicko Scale.